Miles of trees blur past my car window, the pine and oak forests occasionally giving way to open fields where cattle, horses, and the occasional goat graze. The soft murmur of my parents’ voices carries to the back of the Honda Odyssey, where my sister sleeps in the middle row. My brother can’t resist poking her or tugging at her blanket, trying to annoy her as always. I sit in the back row, meanwhile, with my youngest sister, both of us growing impatient as we wait to finally reach our grandparents’ house.

“Are we there yet? Are we there yet? Are we there yet,” I ask my mom again and again.

“No,” she responds, understandably irritated. “We are not there yet. We haven’t even passed the dinosaur.”

I let out a deep sigh and roll my eyes. This trip feels like it’s dragging on for five hours instead of the true two and a half.

Then I see it: the thirty-foot-long, headless dinosaur looming menacingly, ready to devour anyone brave enough to challenge it — if only it had a mouth.

I take in the sight of the dinosaur, trying to capture a quick photo before it slips past my window, already looking forward to the next time I catch a glimpse.

For over 50 years, the headless dinosaur has stood as a cherished symbol of Hernando County’s history. For many, it evokes fond childhood memories and a deep sense of nostalgia. More than just a relic of the past, it serves as a shared experience that brings people together, connecting generations through a common landmark.

However, each time I pass the dinosaur, I notice something new: A fresh hole in its side. More wear on the front. Another missing piece of its tail. How much longer, I sometimes wonder, will this headless relic endure? Will I have the chance to share this piece of my childhood with my children or grandchildren? Or, like so many other lost landmarks, will it simply fade into memory?

—-

August F. Herwede, a painter and interior designer, attended the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, where he came across an exhibit called “Dinoland.” It was a recreation of life as it existed 165 million years ago. Dinosaurs ranging from 6 feet to a massive 70 feet in length, with some standing as tall as 27 feet, loomed over the fairgrounds.

The Dinoland exhibit was sponsored by the Sinclair Oil Corporation, a prominent American oil and gas company that to this day features plastic, green, long-necked dinosaurs outside many of its fill-up stations.

As visitors wandered through the park, they could encounter nine life-size fiberglass dinosaurs, including an Ankylosaurus, Struthiomimus, Trachodon and a duck-billed Corythosaurus. On the right side of Dinoland, a series of booths featured Mold-a-Rama machines, which allowed people to make their own dinosaurs out of liquid plastics. Within the park, a 45-foot-long exhibit brought the prehistoric world to life with erupting volcanoes, flashing lightning, and bubbling streams, depicting Earth’s various stages of formation.

After the exhibit closed in 1965, Sinclair took its dinosaurs on tour as a traveling exhibit. They even made an appearance in the 1966 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

After visiting Dinoland, Herwede, a skilled sculptor and a Swede with a thick accent, was inspired by the gargantuan statues and decided to turn his front yard into a concrete menagerie. Well into his 70s at the time, he crafted over 30 animal sculptures, including an elephant, a woolly mammoth, a pair of lions, and battling dinosaurs.

His most ambitious creation was a huge cement Brontosaurus, realistic in design but missing its head and neck. Intricate lines were carefully carved into the dinosaur’s skin, while hand-molded spikes lined its tail. Its surface remained the raw gray of unfinished cement. A hole in the dinosaur’s belly allowed Herwede to access its center, where a set of stairs ascends into the tail.

While Herwede’s wife was alive, she discouraged him from creating sculptures because it was dangerous, and she feared what could happen to him. But after her passing, he fully embraced his passion.

Herwede began by crafting small pieces like birdbaths and small animals before gradually progressing to dinosaurs. Over time, his creations became increasingly lifelike, capturing the bulging muscles beneath the skin, the texture of hair, and intricate details that brought his sculptures to life.

Alan Waller, who lived near the headless dinosaur his entire life said when he passed Herwede’s house, he would sometimes catch glimpses of the many animals Herwede had created. He noticed that with each new addition, the designs became more refined, with the Brontosaurus standing out as the most impressive.

“The big one just seemed to be really crème de la crème of the street.”

When Waller first saw the dinosaur, he was amazed by how realistic it was.

“That was the crowning jewel,” he said.

In the late summer of 1966, while working on his most ambitious project, the Brontosaurus, Herwede fell from the scaffolding, breaking both legs and his hip. Several hours later, neighbors discovered him and rushed him to the hospital. He passed away a few months later from a heart attack on his couch at the age of 80.

After Herwede’s passing, his collection of animal sculptures was sold off piece by piece and scattered around the front yards of other homes in the area as well as attractions, parks, and even a golf course. Eventually, all that remained was the half-finished Brontosaurus.

Waller’s favorite of Herwede’s statues was the headless dinosaur, not only for his skill but for what it symbolized—it was his passion, yet it also led to his death.

“It represented his life and his death,” Waller said.

Now, more than 50 years later, the unfinished headless dinosaur still stands alone along a bend on State Road 476, slowly being eroded by the elements.

The dinosaur’s large presence has faded into the landscape for those who live there and see it every day.

Which isn’t to say it is not beloved. It is a symbol of Hernando’s uniqueness and history, after all. For the people who live nearby, it is a symbol of home.

—-

After enduring decades of sun and surviving multiple hurricanes over its 50-year lifespan, the dinosaur is beginning to show its age.

With the head unfinished, the headless dinosaur’s exposed interior has long been vulnerable to rain, causing the supports to rot and weakening the concrete. Additionally, the dinosaur was never properly sealed, leading to cracks across its surface. The weather is causing the headless dinosaur to slowly deteriorate.

When I last visited, I noticed its top and sides are riddled with tiny holes, allowing light to filter through. In spots where the plaster was worn thin, the underlying screening was visible.

Years ago, its tail broke off, leaving it both headless and tailless. The tail now rests against a nearby fence, with only a few wires still connecting it to the dinosaur’s body. Local kids have turned the remaining spikes along its back and tail into a game, gradually stripping the ridges bare. Climbing into the hollow of the dinosaur’s belly, I found the floor scattered with rusted rebar, fallen leaves, and crumbling bits of cement. On the left side, a small alcove had become a makeshift trash can, filled with discarded beer cans and seltzer bottles left behind by past visitors.

Travis Wright, a concrete specialist, said that the dinosaur may have only five to ten years before it poses a real safety concern.

When Herwede was building the dinosaur, he likely began by constructing a cage from rebar or steel, then shaped its form using a malleable material like wire and reinforced it with additional steel, said Wright. Herwede then hand-stacked the concrete along the exterior, carefully sketching the skin’s details and textures himself.

Wright, who has worked with concrete for 15 years, has great respect for Herwede’s mastery of the medium.

“A very, very talented individual did that,” he said.

The dinosaur requires several repairs, including fixing cracked, chipped and deteriorating concrete and resealing the structure to protect it from heat and UV damage. Any exposed and rusting rebar would also need to be removed to prevent further decay.

The overall cost of repair, Wright estimated, would be around a couple of thousand dollars. However, the cost to finish the dinosaur would be about $10,000, maybe even $15,000.

Currently, the county does not have any plans to preserve the dinosaur.

Mike Steele, a code enforcement officer, said that because the headless dinosaur is located in a rural area, sits on private property, and is considered art, it is protected under various laws and regulations. It would likely be seen as a hazard only if multiple people were injured.

“It (the headless dinosaur) would probably be more inclined to be deemed anything other than ugly,” he said. “It adds to some of the mystique and uniqueness that is Brooksville.”

Steve Fluker, who has been driving past the dinosaur since he was a kid, said he would love to see a Historical Marker placed there telling the story of Herwede’s creations.

“I think that would keep the memory alive,” he said.

(Photo Courtesy of Steve Fluker)

—-

While some communities use water towers as a unique expression of identity and history, dinosaurs have become a defining symbol of Hernando.

Another notable dinosaur in the area is Dino, a towering, 47-foot-tall, 110-foot-long figure that houses Harold’s Auto Center. It was originally built in 1964 as a Sinclair gas station, when dinosaurs were all the rage. Dino became so popular that Harold’s Auto Center began offering T-shirts and hats in response to customer demand.

Harold’s Auto Center owner Dana Hurst said that maintaining the dinosaur is like caring for an upside-down swimming pool. Most of the repairs consist of pressure washing and patching minor damage. The biggest threat to the dinosaur, Hurst said, is the relentless Florida sunshine.

Both dinosaurs play a key role in the area’s identity, serving as landmarks that help people navigate and connect with the community.

“People say go down past the dinosaur,” Hurst said. “They use it as a landmark to give directions.”

A few years ago, Daniel Pritz, owner of the local Hernando coffee shop Mountaineer Coffee, decided to create a line of shirts that captured the unconventional charm that makes Hernando County unique.

Pritz, a Brooksville native, grew up around the dinosaur and as a kid, he would often pass the dinosaur on the way to church. It became a staple in his life.

Pritz said he decided to create a T-shirt using the headless dinosaur to highlight the quirky things about a small town.

“An ode-to-Brooksville-being-weird sort of thing,” he said.

For Pritz, highlighting the dinosaur was essential because if people stop talking about the dinosaur, it will eventually be forgotten, left to deteriorate until Florida’s landscape reclaims it.

(Photo Courtesy of Steve Fluker)

—-

The headless dinosaur has become a roadside attraction, drawing the attention of passersby who often stop to take photos or admire the structure.

Kevin Eaton, the brother of the dinosaur’s owner, Steve Eaton, said they see around 10 to 20 visitors a day stopping to take a closer look. Steve Eaton received the property where the dinosaur stands as a wedding gift several years ago. Since then, he hasn’t made any changes to it, allowing the dinosaur to remain untouched on his land.

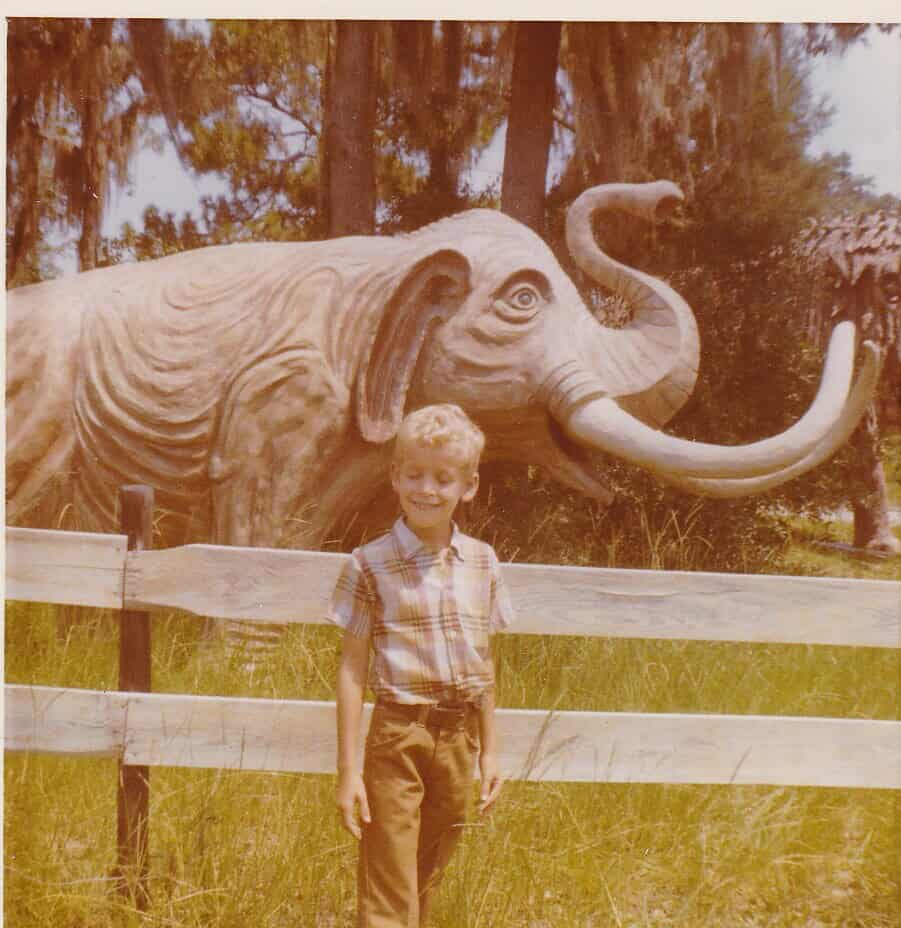

One of those visitors, Fluker, a St. Petersburg resident, first saw the headless dinosaur in the 1960s while traveling to his grandparents’ river house, and it has remained a nostalgic reminder of his childhood. He fondly recalls driving past it around the age of six on trips to visit his grandparents in Nobleton along the Withlacoochee River.

“We really looked forward to when we were driving on that road,” he said.

At times, Fluker’s parents would stop by the dinosaur, allowing him and his brother to climb and play on the various animals in Herwede’s yard.

“It was a landmark that we would know that we’re almost to our house,” he said.

To Fluker, the headless dinosaur is a memorial to Herwede, marking the place where he spent his final days doing what he loved. Each time he passes the dinosaur, he’s reminded of Herwede. It saddens him to know that Herwede never saw his most ambitious project completed, yet it also brings back fond memories of childhood to reflect on.

“I wish he had been able to finish it.”

—-

While the dinosaur is full of fond memories, each missing scale and new hole serves as a reminder that the headless dinosaur’s time is running out.

The dinosaur is more than just a statue. It’s a bridge between generations, connecting people through a shared experience. My dad grew up passing the dinosaur every time he drove down 476, often linking it with fun trips to places like Daytona Beach or canoeing on the Withlacoochee River. For me, as a kid, it marked the start of visits to my grandparents’ house, playing with cousins, eating spinach artichoke dip, and swimming in their pool.

If the dinosaur were to fall tomorrow, future generations wouldn’t understand or feel the same connection my parents and I share. To my kids, it would just be a place their mom always points out as they pass the empty spot where the dinosaur once stood.

Every community should have a quirky symbol, something that sets it apart and captures its unique spirit. Paris has the Eiffel Tower. New York has the Statue of Liberty. Los Angeles has the Hollywood sign. And Hernando County — for now and, hopefully, for much longer — has something truly unique: A giant, headless dinosaur that, despite the pressures of time, refuses to go extinct.