Can you imagine feeling like a foreigner in your own country? How would you like to fight for recognition every single day?

Jovita Idar felt as if she were in a constant daily battle. As a Mexican-American and a young woman of the early 1900s, she was treated as a second-class citizen at best. She spent her entire life trying to change attitudes and mindsets. She refused to back down from a fight against injustice!

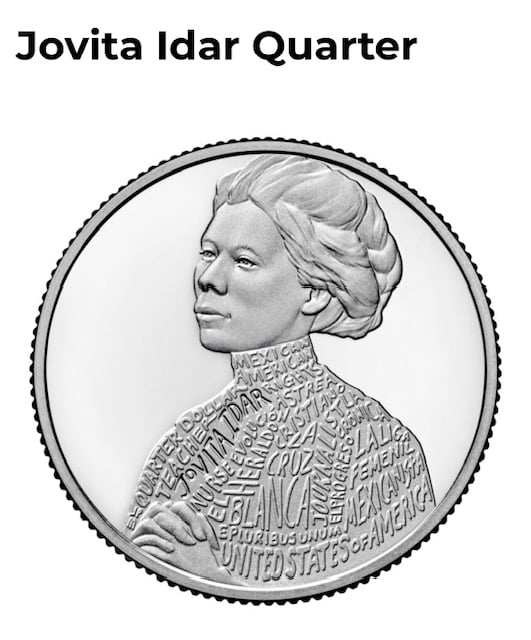

Jovita Idar is remembered as a teacher, journalist, political activist, and civil rights worker. Soon, you’ll notice her likeness on the coins in your pocket. She is the fourth in the American Women’s Quarter Series for 2023. On August 15th, the US Mint released her quarter in honor of her lifelong fight for better education and the empowerment of all people.

But first, a bit of the “back story.” Did you know that Texas wasn’t part of the United States in the early 1800s? It was a portion of some Mexican-owned territories. From 1821–1836, it was called Mexican Texas, along with various other domains spread out from the mid-west to the Pacific Ocean. The Mexican government encouraged Americans to come see and settle. It wasn’t long before Americans outnumbered Tejanos four to one in Mexican Texas. However, few had an interest in being good citizens of Mexico.

By the 1830s, there was talk of breaking away from Mexican control. A new republic would be nice! Most American settlers in Mexican Texas still had cultural ties to the United States. They spoke English (not Spanish) and retained their American customs.

They were also slave owners and wanted to keep it that way. However, Mexico abolished slavery in 1829 (a full 34 years before Abraham Lincoln). It was rumored that other changes were coming soon, giving more power to the Mexican government. Where would this leave the American settlers?

The Texas Revolution (or War of Texas Independence) was fought from October 1835 to April 1836 to gain independence from Mexico. The Republic of Texas then existed as a free territory for nearly ten years before joining the United States. “Texas” became our 28th state on December 29, 1845. Unfortunately, slavery came with it.

Hard feelings remained from the War of Texas. Anglo-Americans didn’t want to associate with Mexican-Americans. They harbored resentment toward them, and yes, even hatred! Many signs in Texas said “NO Mexican-Americans” and “NO Negroes.” Both were not welcome in stores and restaurants.

Meanwhile, most Mexican Americans lived in poverty and were told not to complain. They kept quiet, and with good reason. They even avoided speaking Spanish in public. Those who had spoken up or caused trouble would then face terrible fates. They might be burned, dragged, or even lynched to serve as an example to others.

Violence and discrimination were a way of life in Laredo, Texas, when Jovita Idar was born on September 7, 1885. Her parents were successful professionals, and she was one of eight children. Her family was considered part of the “gente decente,” or people of wealth. This afforded them better access to education and more opportunities. Jovita’s father was the editor of a local newspaper, La Cronica, and was a civil rights advocate. It was from watching him that Jovita learned to be a champion for justice.

Jovita attended a Methodist school and had a strong faith. In 1903, she earned a teaching certificate and took a job in the tiny town of Los Ojuelos, Texas. As a teacher, she saw firsthand the deplorable conditions of Mexican-American schools. Buildings were falling apart; supplies and books were scarce. The textbooks of the day taught a one-sided history lesson. Mexicans were portrayed as the “bad guys,” and Davy Crockett and his Texas defenders were the “good guys.”

Jovita resigned from teaching after a few years and began working at her father’s paper, La Cronica, along with two of her brothers. She felt she could accomplish more in journalism. Their newspaper published stories and editorials that touched on poverty, segregation, and social injustice. They paid particular attention to the plight of Mexican Americans. Jovita wrote many articles and editorials using a pseudonym to disguise her gender. She chose two different pseudonyms. One was A.V. Negra, meaning Blackbird and the other was Astrea, for the Greek god of justice.

In 1911, Jovita and her family organized the First Mexican Congress. They addressed social, economic, and educational issues. The Congress brought together like-minded individuals who wanted to improve conditions for Mexicans and Mexican-Americans.

That same year (1911), Jovita was the first president of the League of Mexican Women.

She invited other women to join the suffrage movement, lobbying for equal rights for women and the right to vote. It was not until 1919 that women could vote in Texas; it was the first Southern state to ratify the 19th Amendment, giving women that right.

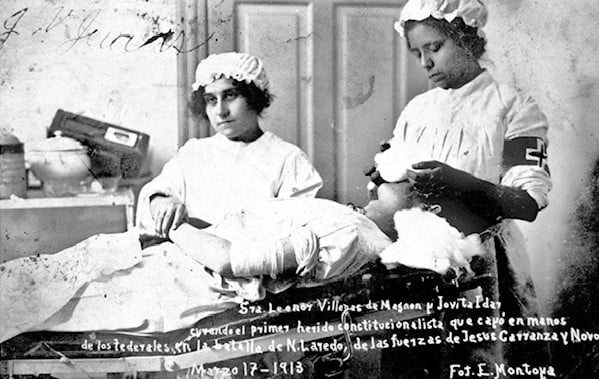

In 1913, as part of La Cruz Blanca (similar to our Red Cross), Jovita bravely volunteered to cross the Rio Grande to treat wounded soldiers during the Mexican Revolution. (1910-1920). In 1914, she protested President Woodrow Wilson’s sending US troops to the border and wrote several articles supporting the Mexican Revolution.

One often-repeated story regarding Jovita Idar happened in 1914 while she was writing for a Laredo newspaper called El Progreso. She single-handedly stood up to a team of Texas Rangers! They had arrived with orders to shut down the newspaper following the publication of an editorial severely criticizing President Wilson. The last thing the Texas Rangers expected to face was a thin 29-year-old journalist blocking the doorway and bidding them to leave! They left, but only temporarily. The Rangers returned on another day when Jovita and staff were gone and smashed the printing press with hammers. They ransacked the newspaper office and effectively shut down El Progreso.

In 1917, Jovita married Bartolo Juarez and, within a few years, moved to San Antonio, Texas, where she would spend the remainder of her life. She had no children but helped raise the two daughters of her late sister, Elvira.

Jovita continued helping and serving. She was a hospital interpreter for Spanish-speaking patients and even taught infant care courses for women. She set up a free kindergarten, too, all while remaining in journalism. Jovita edited a Methodist Church newspaper called El Heraldo and believed that education was the key to a better life.

On June 15, 1946, Jovita Idar died suddenly in San Antonio. The cause of death was a pulmonary hemorrhage and advanced tuberculosis. She was just 60 years old. The New York Times later ran a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths went unreported in the Times. In 2020, Jovita Idar was included as just such an “overlooked” person.

Look closely at the Jovita Idar quarter when you find one. She has many inscriptions on her clothing. Can you recognize the words? Teacher, nurse, and journalist are imprinted there. So are the names of some of her newspapers – Evolucion, El Heraldo Cristiano, La Cronica, and El Progreso. And just below her chin, you see the words “Mexican American Rights,” her lifelong cause.

“Educate a woman, and you educate a family.” — Jovita Idar

Photo by E, Montoya, courtesy of the University of Texas at San Antonio Special Collections.